Social Psychology (10th Edition)

10th Edition

ISBN: 9780134641287

Author: Elliot Aronson, Timothy D. Wilson, Robin M. Akert, Samuel R. Sommers

Publisher: Pearson College Div

expand_more

expand_more

format_list_bulleted

Question

What does Tanner say this chapter is about on the text.

Transcribed Image Text:ว

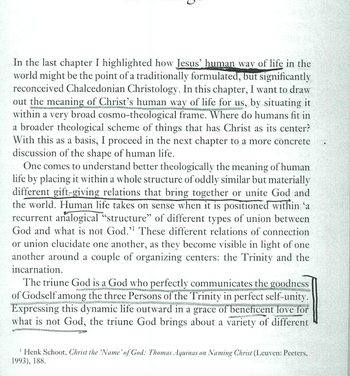

In the last chapter I highlighted how Jesus' human way of life in the

world might be the point of a traditionally formulated, but significantly

reconceived Chalcedonian Christology. In this chapter, I want to draw

out the meaning of Christ's human way of life for us, by situating it

within a very broad cosmo-theological frame. Where do humans fit in

a broader theological scheme of things that has Christ as its center?

With this as a basis, I proceed in the next chapter to a more concrete

discussion of the shape of human life.

One comes to understand better theologically the meaning of human

life by placing it within a whole structure of oddly similar but materially

different gift-giving relations that bring together or unite God and

the world. Human life takes on sense when it is positioned within 'a

recurrent analogical "structure" of different types of union between

God and what is not God." These different relations of connection

or union elucidate one another, as they become visible in light of one

another around a couple of organizing centers: the Trinity and the

incarnation.

The triune God is a God who perfectly communicates the goodness

of Godself among the three Persons of the Trinity in perfect self-unity.

Expressing this dynamic life outward in a grace of beneficent love for

what is not God, the triune God brings about a variety of different

Henk Schoot, Christ the 'Name' of God: Thomas Aquinas on Naming Christ (Leuven: Peeters,

1993), 188.

![JESUS, HUMANITY AND THE TRINITY

forms of connection or union with the non-divine, for the sake of

perfecting what is united with God, in an effort to repeat the perfec-

3 tion of God's own triune life. 'God, full beyond all fulness, brought

creatures into being.

... so that they might participate in Him in

proportion to their capacity and that He Himself might rejoice in His

works... through seeing them joyful and ever filled to overflowing

with His inexhaustible gifts." In a variety of distinct forms of

connection or union in the gift-giving effort, God's work begins with

creation, continues in historical fellowship with a particular people,

Israel, and ends with Jesus as the one through whom, in the Spirit, all

people and the whole world will show forth God's own triune goodness

in unity with God. The incarnation is the perfect form of such relations

of connection or union for gift-giving ends: 'it belongs to the essence

of the highest good [that is, God] to communicate itself in the highest

manner to the creature, and this is brought about chiefly by His so

joining created nature to Himself that one Person is made up.

Hence, it was fitting that God should become incarnate In order

for the whole of the human and natural worlds to be perfected with

God's own gifts, they must be assimilated to this perfect relation

between God and the created world in Christ, by way of him. Indeed,

the Word, with the Spirit, sent by the Father, has, since the begin-

ning of the world in diverse fashions, been working for the embodi-

ment of God's goodness in it. By assuming human nature in all its

embodied connectedness and embeddedness in its physical surround-

ings, the Word in Christ joins the human as well as the natural world

with God.

It is in the body that we stand in solidarity with the whole material creation.

All this God has taken into himself, in sharing man's bodily condition of weak-

ness and limitation: 'O marvellous device of divine wisdom and love, uniting

things lowest with the highest, human with the divine, through our nature,

the least and last and sunken lower still, raising up the whole universe into

union with himself, encircling and enfolding all with his love, and knitting all

in one; and that through us!"+

Maximus the Confessor, "Third Century of Love,' trans. G. Palmer, P. Sherrard, and

K. Ware, in The Philokalia, vol. 2 (London: Faber & Faber, 1981), section 46.

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, trans. Dominican Fathers (Westminster, Maryland:

Christian Classics, 1981), IIIa, Q. 1, A. 1, body.

A. M. Allchin, Participation in God (Wilton, Connecticut: Morehouse-Barlow, 1988), 60,

citing E. B. Pusey's Sermons (1845), 294.

36

THE THEOLOGICAL STRUCTURE OF THINGS

Human beings who are one with Christ, by the Spirit, further the effort

for all people and for the cosmos as a whole in recognition of their

essential links with all others and their inextricable being in the midst

of the natural world. Thus, 'we have always to remember that God's

glory really consists in His self-giving, and that this has its centre and

meaning in God's Son, Jesus Christ, and that the name of Jesus Christ

stands for the event in which man, and in man the whole cosmos, is

awakened and called and enabled to participate in the being of God.”

Through Christ, human beings have a crucial mediatorial role to play

in God's gift-giving ends for one another and the whole world: 'In his

way to union with God, man in no way leaves creatures aside, but

gathers in his love the whole cosmos disordered by sin, that it may at

last be transfigured by grace." God's whole effort to share God's

trinitarian life with the world, with all its many distinct facets, is in

this way focused in Christ: 'The incarnation of the Word of God at

Bethlehem, in Galilee, in Jerusalem, is not an isolated wonder, but a

central focal point in a network of divine initiatives which spread out

into the whole of human history, indeed into the whole universe."

Situated within this theological structure of many different parallel

or analogous relations of gift-giving unity, human life - indeed, any

aspect of the structure (say, Christ himself on the account I offered

in the last chapter) - gains a greater intelligibility, as each aspect

becomes a kind of commentary on the others. Intelligibility here is

like that of myth according to Claude Lévi-Strauss, where conundrums

are naturalized, rather than resolved, by repeating them across a variety

of domains. Or it is like the intelligibility provided by a Freudian

Karl Barth, Church Dugmatics II/1, trans. G. W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance (Edinburgh:

T&T Clark, 1957), 670.

"Vladimir Lossky, The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church (Crestwood, New York: St

Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1976), 111, discussing the views of Maximus the Confessor.

A. M. Allchin, Participation in God, 72, discussing Maximus the Confessor. On this as the

view of Bonaventure, see Ewert Cousins, Bonaventure and the Coincidence of Opposites (Chicago:

Franciscan Herald Press, 1979), 206-7: 'although the coincidence of opposites is the universal

logic of Bonaventure's system, each major area of his thought has its own specific form of the

coincidence of opposites based on the metaphysical structure of that area. The notion of Christ

the center, then, accounts for the common logic at the same time that it sustains the specific

difference of each class."

* See Claude Lévi-Strauss' treatment of myth in his Structural Anthropology, trans.

C. Jacobson and B. Schoepf (New York: Basic Books, 1973).

37](https://content.bartleby.com/qna-images/question/2e1cb03f-91d2-4991-91c8-37c8965f1bd7/a8e25137-cd15-4c64-8959-102c3a938bfb/js68xkh_thumbnail.png)

Transcribed Image Text:JESUS, HUMANITY AND THE TRINITY

forms of connection or union with the non-divine, for the sake of

perfecting what is united with God, in an effort to repeat the perfec-

3 tion of God's own triune life. 'God, full beyond all fulness, brought

creatures into being.

... so that they might participate in Him in

proportion to their capacity and that He Himself might rejoice in His

works... through seeing them joyful and ever filled to overflowing

with His inexhaustible gifts." In a variety of distinct forms of

connection or union in the gift-giving effort, God's work begins with

creation, continues in historical fellowship with a particular people,

Israel, and ends with Jesus as the one through whom, in the Spirit, all

people and the whole world will show forth God's own triune goodness

in unity with God. The incarnation is the perfect form of such relations

of connection or union for gift-giving ends: 'it belongs to the essence

of the highest good [that is, God] to communicate itself in the highest

manner to the creature, and this is brought about chiefly by His so

joining created nature to Himself that one Person is made up.

Hence, it was fitting that God should become incarnate In order

for the whole of the human and natural worlds to be perfected with

God's own gifts, they must be assimilated to this perfect relation

between God and the created world in Christ, by way of him. Indeed,

the Word, with the Spirit, sent by the Father, has, since the begin-

ning of the world in diverse fashions, been working for the embodi-

ment of God's goodness in it. By assuming human nature in all its

embodied connectedness and embeddedness in its physical surround-

ings, the Word in Christ joins the human as well as the natural world

with God.

It is in the body that we stand in solidarity with the whole material creation.

All this God has taken into himself, in sharing man's bodily condition of weak-

ness and limitation: 'O marvellous device of divine wisdom and love, uniting

things lowest with the highest, human with the divine, through our nature,

the least and last and sunken lower still, raising up the whole universe into

union with himself, encircling and enfolding all with his love, and knitting all

in one; and that through us!"+

Maximus the Confessor, "Third Century of Love,' trans. G. Palmer, P. Sherrard, and

K. Ware, in The Philokalia, vol. 2 (London: Faber & Faber, 1981), section 46.

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, trans. Dominican Fathers (Westminster, Maryland:

Christian Classics, 1981), IIIa, Q. 1, A. 1, body.

A. M. Allchin, Participation in God (Wilton, Connecticut: Morehouse-Barlow, 1988), 60,

citing E. B. Pusey's Sermons (1845), 294.

36

THE THEOLOGICAL STRUCTURE OF THINGS

Human beings who are one with Christ, by the Spirit, further the effort

for all people and for the cosmos as a whole in recognition of their

essential links with all others and their inextricable being in the midst

of the natural world. Thus, 'we have always to remember that God's

glory really consists in His self-giving, and that this has its centre and

meaning in God's Son, Jesus Christ, and that the name of Jesus Christ

stands for the event in which man, and in man the whole cosmos, is

awakened and called and enabled to participate in the being of God.”

Through Christ, human beings have a crucial mediatorial role to play

in God's gift-giving ends for one another and the whole world: 'In his

way to union with God, man in no way leaves creatures aside, but

gathers in his love the whole cosmos disordered by sin, that it may at

last be transfigured by grace." God's whole effort to share God's

trinitarian life with the world, with all its many distinct facets, is in

this way focused in Christ: 'The incarnation of the Word of God at

Bethlehem, in Galilee, in Jerusalem, is not an isolated wonder, but a

central focal point in a network of divine initiatives which spread out

into the whole of human history, indeed into the whole universe."

Situated within this theological structure of many different parallel

or analogous relations of gift-giving unity, human life - indeed, any

aspect of the structure (say, Christ himself on the account I offered

in the last chapter) - gains a greater intelligibility, as each aspect

becomes a kind of commentary on the others. Intelligibility here is

like that of myth according to Claude Lévi-Strauss, where conundrums

are naturalized, rather than resolved, by repeating them across a variety

of domains. Or it is like the intelligibility provided by a Freudian

Karl Barth, Church Dugmatics II/1, trans. G. W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance (Edinburgh:

T&T Clark, 1957), 670.

"Vladimir Lossky, The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church (Crestwood, New York: St

Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1976), 111, discussing the views of Maximus the Confessor.

A. M. Allchin, Participation in God, 72, discussing Maximus the Confessor. On this as the

view of Bonaventure, see Ewert Cousins, Bonaventure and the Coincidence of Opposites (Chicago:

Franciscan Herald Press, 1979), 206-7: 'although the coincidence of opposites is the universal

logic of Bonaventure's system, each major area of his thought has its own specific form of the

coincidence of opposites based on the metaphysical structure of that area. The notion of Christ

the center, then, accounts for the common logic at the same time that it sustains the specific

difference of each class."

* See Claude Lévi-Strauss' treatment of myth in his Structural Anthropology, trans.

C. Jacobson and B. Schoepf (New York: Basic Books, 1973).

37

Expert Solution

This question has been solved!

Explore an expertly crafted, step-by-step solution for a thorough understanding of key concepts.

Step by stepSolved in 2 steps

Knowledge Booster

Recommended textbooks for you

Social Psychology (10th Edition)SociologyISBN:9780134641287Author:Elliot Aronson, Timothy D. Wilson, Robin M. Akert, Samuel R. SommersPublisher:Pearson College Div

Social Psychology (10th Edition)SociologyISBN:9780134641287Author:Elliot Aronson, Timothy D. Wilson, Robin M. Akert, Samuel R. SommersPublisher:Pearson College Div Introduction to Sociology (Eleventh Edition)SociologyISBN:9780393639407Author:Deborah Carr, Anthony Giddens, Mitchell Duneier, Richard P. AppelbaumPublisher:W. W. Norton & Company

Introduction to Sociology (Eleventh Edition)SociologyISBN:9780393639407Author:Deborah Carr, Anthony Giddens, Mitchell Duneier, Richard P. AppelbaumPublisher:W. W. Norton & Company The Basics of Social Research (MindTap Course Lis...SociologyISBN:9781305503076Author:Earl R. BabbiePublisher:Cengage Learning

The Basics of Social Research (MindTap Course Lis...SociologyISBN:9781305503076Author:Earl R. BabbiePublisher:Cengage Learning Criminalistics: An Introduction to Forensic Scien...SociologyISBN:9780134477596Author:Saferstein, RichardPublisher:PEARSON

Criminalistics: An Introduction to Forensic Scien...SociologyISBN:9780134477596Author:Saferstein, RichardPublisher:PEARSON Sociology: A Down-to-Earth Approach (13th Edition)SociologyISBN:9780134205571Author:James M. HenslinPublisher:PEARSON

Sociology: A Down-to-Earth Approach (13th Edition)SociologyISBN:9780134205571Author:James M. HenslinPublisher:PEARSON Society: The Basics (14th Edition)SociologyISBN:9780134206325Author:John J. MacionisPublisher:PEARSON

Society: The Basics (14th Edition)SociologyISBN:9780134206325Author:John J. MacionisPublisher:PEARSON

Social Psychology (10th Edition)

Sociology

ISBN:9780134641287

Author:Elliot Aronson, Timothy D. Wilson, Robin M. Akert, Samuel R. Sommers

Publisher:Pearson College Div

Introduction to Sociology (Eleventh Edition)

Sociology

ISBN:9780393639407

Author:Deborah Carr, Anthony Giddens, Mitchell Duneier, Richard P. Appelbaum

Publisher:W. W. Norton & Company

The Basics of Social Research (MindTap Course Lis...

Sociology

ISBN:9781305503076

Author:Earl R. Babbie

Publisher:Cengage Learning

Criminalistics: An Introduction to Forensic Scien...

Sociology

ISBN:9780134477596

Author:Saferstein, Richard

Publisher:PEARSON

Sociology: A Down-to-Earth Approach (13th Edition)

Sociology

ISBN:9780134205571

Author:James M. Henslin

Publisher:PEARSON

Society: The Basics (14th Edition)

Sociology

ISBN:9780134206325

Author:John J. Macionis

Publisher:PEARSON