Social Psychology (10th Edition)

10th Edition

ISBN: 9780134641287

Author: Elliot Aronson, Timothy D. Wilson, Robin M. Akert, Samuel R. Sommers

Publisher: Pearson College Div

expand_more

expand_more

format_list_bulleted

Question

How is the Christian’s being assumed by Christ (p. 71) evident in human action?

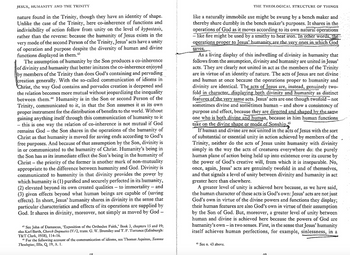

Transcribed Image Text:JESUS, HUMANITY AND THE TRINITY

nature found in the Trinity, though they have an identity of shape.

Unlike the case of the Trinity, here co-inherence of functions and

indivisibility of action follow from unity on the level of hypostasis,

rather than the reverse: because the humanity of Jesus exists in the

very mode of the second Person of the Trinity, Jesus' acts have a unity

of operation and purpose despite the diversity of human and divine

functions displayed in them.+3

The assumption of humanity by the Son produces a co-inherence

of divinity and humanity that better imitates the co-inherence enjoyed

by members of the Trinity than does God's containing and pervading

creation generally. With the so-called communication of idioms in

"Christ, the way God contains and pervades creation is deepened and

the relation becomes more mutual without jeopardizing the inequality

between them." Humanity is in the Son or second Person of the

Trinity, communicated to it, in that the Son assumes it as its own

proper instrument for the distribution of benefits to the world. Without

gaining anything itself through this communication of humanity to it

this is one way the relation of co-inherence is not mutual if God

remains God the Son shares in the operations of the humanity of

Christ as that humanity is moved for saving ends according to God's

free purposes. And because of that assumption by the Son, divinity is

in or communicated to the humanity of Christ. Humanity's being in

the Son has as its immediate effect the Son's being in the humanity of

Christ the priority of the former is another mark of non-mutuality

appropriate to the difference between humanity and God. Divinity is

communicated to humanity in that divinity provides the power by

which humanity is (1) purified and securely perfected in its humanity,

(2) elevated beyond its own created qualities to immortality - and

(3) given effects beyond what human beings are capable of (saving

effects). In short, Jesus' humanity shares in divinity in the sense that

particular characteristics and effects of its operations are supplied by

God. It shares in divinity, moreover, not simply as moved by God -

-

--

*See John of Damascus, 'Exposition of the Orthodox Faith,' Book 3, chapters 15 and 19;

also Karl Barth, Church Dugmatics IV/2, trans. G. W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance (Edinburgh:

T&T Clark, 1958), 114–16.

For the following account of the communication of idioms, see Thomas Aquinas, Summa

Theologiae, IIIa, Q. 19, A. 1.

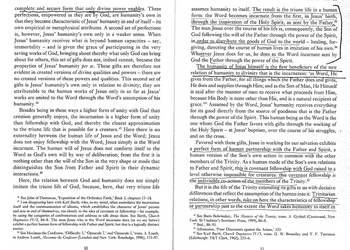

THE THEOLOGICAL STRUCTURE OF THINGS

like a naturally immobile axe might be swung by a bench maker and

thereby share dumbly in the bench maker's purposes. It shares in the

operations of God as it moves according to its own natural operations

-like fire might be used by a smithy to heat iron. In other words, the

operations proper to Jesus' humanity are the very ones in which God

saves.

As a living display of this indwelling of divinity in humanity that

follows from the assumption, divinity and humanity are united in Jesus'

acts. They are clearly not united in act as the members of the Trinity

are in virtue of an identity of nature. The acts of Jesus are not divine

and human at once because the operations proper to humanity and

divinity are identical. The acts of Jesus are, instead, genuinely two-

fold in character, displaying both divinity and humanity as distinct

features of the very same acts. Jesus' acts are one though twofold - not

sometimes divine and sometimes human - and show a consistency of

purpose and effect, because they are directed and shaped by the same

one who is both divine and human, because in him human functions

take on the divine shape or mode of Sonship

45

If human and divine are not united in the acts of Jesus with the sort

of substantial or essential unity in action achieved by members of the

Trinity, neither do the acts of Jesus unite humanity with divinity

simply in the way the acts of creatures everywhere do: the purely

human plane of action being held up into existence over its course by

the power of God's creative will, from which it is inseparable. No,

once, again, Jesus' acts are genuinely twofold in and of themselves,

and that signals a level of unity between divinity and humanity in act

greater here than elsewhere.

A greater level of unity is achieved here because, as we have said,

the human character of these acts is God's own: Jesus' acts are not just

God's own in virtue of the divine powers and functions they display;

their human features are also God's own in virtue of their assumption

by the Son of God. But, moreover, a greater level of unity between

human and divine is achieved here because the powers of God are

humanity's own - in two senses. First, in the sense that Jesus' humanity

itself achieves human perfections, for example, sinlessness, in a

+3 Sce n. +3 above.

19

10.

Transcribed Image Text:complete and secure form that only divine power enables. These

perfections, empowered as they are by God, are humanity's own in

that they become characteristic of Jesus' humanity in and of itself - its

own empirical or metaphysical attributes. A second set of perfections

is, however, Jesus' humanity's own only in a weaker sense. When

Jesus' humanity receives what is beyond human capacities say,

immortality and is given the grace of participating in the very

saving works of God, bringing about thereby what only God can bring

about for others, this set of gifts does not, indeed cannot, become the

properties of Jesus' humanity per se. These gifts are therefore not

evident in created versions of divine qualities and powers - there are

no created versions of these powers and qualities. This second set of

gifts is Jesus' humanity's own only in relation to divinity; they are

attributable to the human works of Jesus only in so far as Jesus'

works are united to the Word through the Word's assumption of his

humanity.th

Besides being in these ways a higher form of unity with God than

creation generally enjoys, the incarnation is a higher form of unity

than fellowship with God, and thereby the closest approximation

to the triune life that is possible for a creature. . Here there is no

externality between the human life of Jesus and the Word; Jesus

does not enjoy fellowship with the Word; Jesus simply is the Word

incarnate. The human will of Jesus does not conform itself to the

Word as God's own will by way of deliberation; from the first it is

nothing other than the will of the Son in the very shape or mode that

distinguishes the Son from Father and Spirit in their dynamic

interactions.*

Here, the relation between God and humanity does not simply

imitate the triune life of God, because, here, that very triune life

"See John of Damascus, 'Exposition of the Orthodox Faith,' Book 3, chapters 17-18.

*I am disagreeing here with Karl Barth, who, to my mind, often assimilates the incarnation

itself and the communication of idioms, which establishes the character of Jesus' person

and acts in and of themselves, too closely to the idea of covenant or fellowship - for example,

by using the categories of confrontation and address to talk about them. See Barth, Church

Dogmatics IV/2, 84-8. The man Jesus who is the Word incarnate does (as we see below)

exhibit a perfect human form of fellowship with Father and Spirit, but that is a logically distinct

matter.

See Maximus the Confessor, 'Difficulty 5,' 'Oposcule 7,' and 'Oposcule 3,' trans. A. Louth,

in Andrew Louth, Maximus the Confessor (London and New York: Routledge, 1996), 171–97.

50

assumes humanity to itself. The result is the triune life in a human.

form: the Word becomes incarnate from the first, in Jesus' birth,

through the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, as sent by the Father

The man Jesus over the course of his life is, consequently, the Son of

God following the will of the Father through the power of the Spirit,

in order to distribute the goods of God to the world-healing, for-

giving, directing the course of human lives in imitation of his own.50

Whatever Jesus does for us, he does as the Word incarnate sent by

God the Father through the power of the Spirit.

The humanity of Jesus himself is the first beneficiary of the new

relation of humanity to divinity that is the incarnation: 'as Word, He

gives from the Father, for all things which the Father does and gives,

He does and supplies through Him; and as the Son of Man, He Himself

is said after the manner of men to receive what proceeds from Him,

because His Body is none other than His, and is a natural recipient of

grace. 351 Assumed by the Word, Jesus' humanity receives everything

for its good directly from the source of goodness that is the Father

through the power of the Spirit. This human being as the Word is the

one whom God the Father favors with gifts through the working of

the Holy Spirit at Jesus' baptism, over the course of his struggles,

and on the cross.

Favored with these gifts, Jesus in working for our salvation exhibits

a perfect form of human partnership with the Father and Spirit, a

human version of the Son's own action in common with the other

members of the Trinity. As a human mode of the Son's own relations

to Father and Spirit, this is covenant fellowship with God raised to a

level otherwise impossible for creatures: this covenant fellowship is

the indivisible co-action-of the members of the Trinity. 52

But it is the life of the Trinity extending its gifts to us with decisive

differences that reflect the assumption of the human into it. Trinitarian

relations, in other words, take on here the characteristics of fellowship

or partnership just to the extent the Word takes humanity to itself in

See Boris Bobrinskoy, The Mystery of the Trinity, trans. A. Gythiel (Crestwood, New

York: St Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1999), 86-8.

Ibid., 88-93.

Athanasius, 'Four Discourses against the Arians,' 333.

See Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics IV/3, trans. G. W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance

(Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1962), 235–6.

51

Expert Solution

This question has been solved!

Explore an expertly crafted, step-by-step solution for a thorough understanding of key concepts.

Step by stepSolved in 2 steps

Knowledge Booster

Recommended textbooks for you

Social Psychology (10th Edition)SociologyISBN:9780134641287Author:Elliot Aronson, Timothy D. Wilson, Robin M. Akert, Samuel R. SommersPublisher:Pearson College Div

Social Psychology (10th Edition)SociologyISBN:9780134641287Author:Elliot Aronson, Timothy D. Wilson, Robin M. Akert, Samuel R. SommersPublisher:Pearson College Div Introduction to Sociology (Eleventh Edition)SociologyISBN:9780393639407Author:Deborah Carr, Anthony Giddens, Mitchell Duneier, Richard P. AppelbaumPublisher:W. W. Norton & Company

Introduction to Sociology (Eleventh Edition)SociologyISBN:9780393639407Author:Deborah Carr, Anthony Giddens, Mitchell Duneier, Richard P. AppelbaumPublisher:W. W. Norton & Company The Basics of Social Research (MindTap Course Lis...SociologyISBN:9781305503076Author:Earl R. BabbiePublisher:Cengage Learning

The Basics of Social Research (MindTap Course Lis...SociologyISBN:9781305503076Author:Earl R. BabbiePublisher:Cengage Learning Criminalistics: An Introduction to Forensic Scien...SociologyISBN:9780134477596Author:Saferstein, RichardPublisher:PEARSON

Criminalistics: An Introduction to Forensic Scien...SociologyISBN:9780134477596Author:Saferstein, RichardPublisher:PEARSON Sociology: A Down-to-Earth Approach (13th Edition)SociologyISBN:9780134205571Author:James M. HenslinPublisher:PEARSON

Sociology: A Down-to-Earth Approach (13th Edition)SociologyISBN:9780134205571Author:James M. HenslinPublisher:PEARSON Society: The Basics (14th Edition)SociologyISBN:9780134206325Author:John J. MacionisPublisher:PEARSON

Society: The Basics (14th Edition)SociologyISBN:9780134206325Author:John J. MacionisPublisher:PEARSON

Social Psychology (10th Edition)

Sociology

ISBN:9780134641287

Author:Elliot Aronson, Timothy D. Wilson, Robin M. Akert, Samuel R. Sommers

Publisher:Pearson College Div

Introduction to Sociology (Eleventh Edition)

Sociology

ISBN:9780393639407

Author:Deborah Carr, Anthony Giddens, Mitchell Duneier, Richard P. Appelbaum

Publisher:W. W. Norton & Company

The Basics of Social Research (MindTap Course Lis...

Sociology

ISBN:9781305503076

Author:Earl R. Babbie

Publisher:Cengage Learning

Criminalistics: An Introduction to Forensic Scien...

Sociology

ISBN:9780134477596

Author:Saferstein, Richard

Publisher:PEARSON

Sociology: A Down-to-Earth Approach (13th Edition)

Sociology

ISBN:9780134205571

Author:James M. Henslin

Publisher:PEARSON

Society: The Basics (14th Edition)

Sociology

ISBN:9780134206325

Author:John J. Macionis

Publisher:PEARSON