Question

GROWING OPPOSITION TO TSARDOM

1.) Read the attatched pictures to complete the table (in the activity higlighted) to explain why there was growing opposition to tsardom.

2. Using the completed table consider the question: 'How much opposition was there to the Tsar by 1917?' and what was the significance of the opposition?

Transcribed Image Text:52

Russia 1894-1941

Progressive Bloc

In early 1915, the Duma asked

Nicholas Il to replace his cabinet,

which they believed to be

incompetent to deal with the

war, with a 'ministry of national.

confidence. It was argued that

the new body should be made up

of more forward-looking Duma

members. Nicholas rejected the

idea, which caused the proposers to

form a group to persuade the tsar

to adopt more progressive ideas.

consisted of Kadets, Octobrists

id Progressists; they became

own as the 'Progressive Bloc.

politicians as one of the most able Russian administrators of all time but

the tsarina claimed he sympathised with revolutionists. This kind of action

caused much discontent within the government and was part of the reasons

for the formation of a 'Progressive Bloc' in the Duma to put pressure on the

tsar to take firmer control of proceedings.

Rasputin's influence on Russian government

If Rasputin had any influence on Russian government it came through.

his friendship with the tsarina. Through helping her son, Alexei, Rasputin

won over the confidence and admiration of Alexandra. If Rasputin had

wanted to help shape Russian political affairs then he would have done

so by persuading Alexandra to making certain ministerial appointments

or formulating a particular policy. However, there is little evidence to

support this. The main indicator of his interference is when he was asked to

reorganise the army's medical supply system. However, this hardly indicates

that he wanted to shape the direction that Russian government was taking.

Nonetheless, he was obviously seen as having some negative level of

influence over the royal family as he was despised by the tsar's advisers. It

is possible that such ill-feeling was a result of envy; Rasputin does seem to

have shown aptitude as an administrator (as in the case of dealing with the

medical supplies issue).

The role of the Fourth Duma

When the final (fourth) Duma was called (November 1912-February

1917) it was once more dominated by politicians from the far right (ultral

conservatives). Its tenure coincided with heightened and brutal repression of

civil disorder. This was characterised by state police killing striking miners

at the Lena Goldfields (1912) (see page 36). The murders outraged many

Duma members who viewed this as a retrograde step by the government in its

attempt to deal with Russia's economic and social problems. Guchkov (see

page 19), leader of the moderate Octobrists, warned the tsar and ministers

that the Russian people had become revolutionised by the actions of the

government and that they had lost faith in its leaders. In 1914, the Duma

made the following proclamation and prophecy of doom:

The Ministry of the Interior systematically scorns public opinion and ignores

the repeated wishes of the new legislature. The Duma considered it pointless

to express any new wishes in regard to internal policy. The Ministry's activities

arouse dissatisfaction among the broad masses that have hitherto been

peaceful. Such a situation threatens Russia with untold dangers.

Cited in Theofanis Ceorge Stavrou, Russia Under the Last Czar, 1969

The progress of the fourth Duma was interrupted by the outbreak of the

First World War in 1914. The Duma met a week after the start of the war,

but its work was disrupted when a group of socialist members walked out

mainly at Nicholas II's decision to commit Russia to a war they considered

unwinnable. However, initially the Duma had backed the tsar and voted for

its own suspension for the duration of the war but in 1915, with the military

failings it demanded its own recall and met for six weeks before it was

prorogued following its demand for a national government to take charge of

the war effort. Nicholas responded by suspending the Duma in August 1915,

and personally taking charge of the armed forces.

This was the last chance he had of maintaining the support of the

progressive parties. The result was that many members formed the

Progressive Bloc', which criticised the management of the war and

tried to persuade Nicholas to make concessions, but he continued to be

unwilling to listen. As his government proved increasingly incapable of

running the war so the Duma changed from being a supporter at the start

of the war to an opponent. However, despite its criticisms of government

rule, it remained an institution that was dominated by the 'old guard'

(supporters of tsarism and authoritarian rule). The final Dama became

infamous for eventually putting pressure on the tsar to abdicate in March

1917 and went on to form the backbone of the short-lived Provisional

Government.

The decision by Nicholas to go to the front was criticised by many and,

at least in part, this was because it left the unpopular tsarina and Rasputin

in charge of affairs in Petrograd. As neither were trusted by Russia's elite

this further weakened the position of Nicholas and was made worse by the

deteriorating position both on the home front and in the war. Therefore,

although Nicholas' decision might be seen as heroic and an attempt to

strengthen Russia's position, it backfired and played a crucial role in his

downfall.

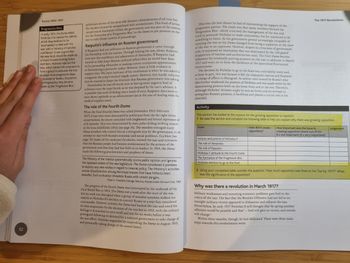

Activity

This section has looked at the reasons for the growing opposition to tsardom.

1 Re-read the section and complete the following table to help you explain why there was growing opposition.

Issue

Actions and policies of Nicholas II

The role of Alexandra

The role of Rasputin

Nicholas II attitude to the Fourth Duma

The formation of the Progressive Bloc

Nicholas decision to go to the front

How did it create

opposition?

The 1917 Revolutions

How important was the issue in

creating opposition (mark out of six:

0= not important; 6 = very important)

Why was there a revolution in March 1917?

Military weaknesses and mounting economic problems gave fuel to the

critics of the tsar. The fact that the Brusilov Offensive had not led to an

outright military victory appeared to dishearten and exhaust the tsar.

Nevertheless, by early 1917 Nicholas II still thought that by spring another

offensive would be possible and that ... God will give us victory, and moods

will change'.

Within three months, though, he had abdicated. There were three main

steps towards this revolutionary event.

Judgement

2 Using your completed table consider the question: 'How much opposition was there to the Tsar by 1917?" What

was the significance of the opposition?

Transcribed Image Text:0

Russia 1894-1941

Alexei Brusilov 1853-1926

Brusilov was a skilled cavalry

officer who fought in the war

against Turkey 1877-78. He

commanded a major offensive

against Austria Hungary in 1916,

which concentrated forces and

used smaller well trained units. He

is regarded as a highly successful

and innovative commander by

military historians

Alexei Kuropatkin 1848-1925

Kuropatkin, as minister of war, had

opposed the war against Japan

1904. He commanded Russian

forces poorly in Manchuria. He

was recalled in 1915 and went on

to mismanage the Northern Front

through costly frontal assaults

and a failure to support more

imaginative commanders. He was

sacked in 1916.

others, with, for example their bread ration falling 25 per cent in the first

three months of 1916. But regional variation is not particularly important

as the social unrest that resulted from high prices and shortages gathered

momentum in the places where it was likely to have the greatest impact-

the growing towns and cities in the west of Russia.

Transport and communications

The war placed severe pressures on the transport system in Russia.

particularly the railways. Lines became blocked, signalling mechanisms broke

down and engines became stranded (often as a result of running out of fuel

Railway stations and depots started to struggle to handle the vast volumes of

freight (mainly munitions and food). As indicated in the sections above, all of

this was to have serious repercussions for the supply of materials and food to

soldiers and civilians.

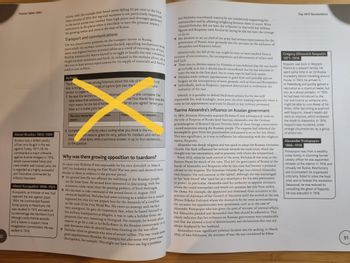

Activity

There is much date among historians about the role of the First World

War in bring about fall of tsarism (see also the storical debate

section on pages b

1 Re-read this section and use the information to help you complete the

table below that addresses we key stion; ine First World War was the

far do you agree? Write your

main reason for the fall of Nicho

ideas out in bullet point form

The First World War was the main

reason...

There were other reasons...

2 Complete the divity by colour coding what you think is the most to

least in portant reasons: green for very, yellow for medium and red for

minir Once done, write a summary answer, in up to four sentences,

to the question.

Why was there growing opposition to tsardom?

In many ways Nicholas II was responsible for his own downfall in March

1917; his leadership during the First World War was poor and showed traits

similar to those in evidence in the pre-war period.

He ignored how the war affected the well-being of the Russian people

on the home front. He seemed more interested in discussing, with his

ministers, trivia rather than the pressing problem of food shortages.

■ His decision to take command of the armed forces in August 1915

obviously backfired. Nicholas had some training as a soldier (in a cavalry

regiment) but this did not prepare him for the demands of a conflict

on the scale of the First World War. His views on strategy and tactics

were unoriginal. He gave the impression that, when he based himself in

the military headquarters at Mogilev, it was to take a holiday from the

pressures that were mounting in Petrograd. For example, he would often

request to go for a ride in his Rolls-Royce in the Russian countryside c

play dominoes when he should have been focusing on the war effort.

Nicholas relied on generals who were of mixed calibre. The tsar made som

good appointments (Brusilov, for example) but also some very poor ones

(Kuropatkin, for example). This might not have been too big a problem

or to

but Nicholas exacerbated matters by not consistently supporting his

commanders and by allowing infighting between them to occur. Witte

claimed Nicholas did not have the willpower to deal with key military

figures and Rasputin went further by saying he did not have the courage

to do so.

His decision to act as chief of the army had serious repercussions for the

governance of Russia more generally (see the sections on the influence of

Alexandra and Rasputin below).

Alternatively, the fall of the tsar might be seen to have resulted from a

mixture of circumstance, the incompetence and deviousness of others and

bad luck.

There was no obvious reason for Nicholas to have believed that the war would

go as badly as it did; it should also be remembered that he was reluctant to

enter the war in the first place, but in many ways he had little option.

■ Nicholas made military appointments in good faith and probably did not

bargain on the incompetency of some generals, such as Evert and Kuropatkin.

Individuals, such as Rasputin, appeared determined to undermine the

authority of the tsar.

Overall, it is possible to defend Nicholas's actions but he was still

responsible for, with hindsight, some poor decision making especially when it

came to the appointment and trust he placed in key military personnel.

Tsarina Alexandra's influence on Russian government

In 1894, Princess Alexandra married Nicholas II and subsequently took on

the title of Empress of Russia (and Tsarina). Alexandra was the German

granddaughter of Britain's Queen Victoria; both of these foreign connections

caused suspicion among the Russian people. The empress had inherited the

haemophilic gene from her grandmother and passed it on to her son Alexei.

This was significant, as it was to influence her relationship with the religious

mystic, Rasputin.

Alexandra was deeply religious and was quick to adopt the Russian Orthodox

Church. Her faith influenced her attitude towards the royal court, which she

thought was too ostentatious, and to peasants, with whom she sympathised.

From 1915, when he took control of the army, Nicholas II was away at the

Eastern Front for much of the time. This left the governance of Russia in the

hands of Alexandra and Rasputin, who by this time had become a personal

adviser to the empress. The historian Orlando Figes has claimed Alexandra

then became the real autocrat in the capital', although she was encouraged

by her 'holy friend' who 'used her as a mouthpiece for his own pretensions

to power'. In particular, Alexandra used her authority to appoint ministers

whom she could manipulate and would not question her role from within

the Duma. For example, she appointed and dismissed three ministers to the

position of chairman of the Council of Ministers until she arrived at the one

(Prince Nikolai Golitsyn) whom she deemed to be the most accommodating.

On occasion her appointments were questioned, such as in the case of

Alexander Protopopov who was given the post of minister of internal affairs,

but Alexandra pleaded and demanded that they should be adhered to. This

clearly indicates that her influence on Russian government was considerable

and that she showed a level of determination and decisiveness that was not

always displayed by her husband.

Alexandra's most significant political decision was the sacking, in March

1916, of Alex Polikanov, the minister of war. He was considered by fellow

The 1917 Revolutions

Gregory Efimovich Rasputin

1871-1916

Rasputin was born in Western

Siberia to a peasant family. He

spent some time in an Orthodox

monastery before travelling around

Russia. In 1903, he arrived in

St Petersburg and quickly gained a

reputation as a mystical healer, but

also as a sexual predator. In 1905,

he had been introduced to the

tsar and tsarina as someone who

might be able to cure Alexei of his

illness. After becoming acquainted

with Rasputin, Alexei's health did

seem to improve, which endeared

the monk to Alexandra. In 1916,

Rasputin was murdered, under

strange circumstances, by a group

of aristocrats.

Alexander Protopopov

1866-1918

Protopopov was from a wealthy

noble family. A charming former

cavalry officer he was appointed

minister of the interior in 1916 and

virtually ran Russia. Reactionary

and incompetent he suppressed

criticisms, failed to solve the food

crisis and to foresee the revolution.

Delusional, he was reduced to

consulting the ghost of Rasputin.

He was executed in 1918.

51

Expert Solution

This question has been solved!

Explore an expertly crafted, step-by-step solution for a thorough understanding of key concepts.

Step by stepSolved in 3 steps